A special report by Accenture analyses the trust and loyalty trends among global banking consumers:

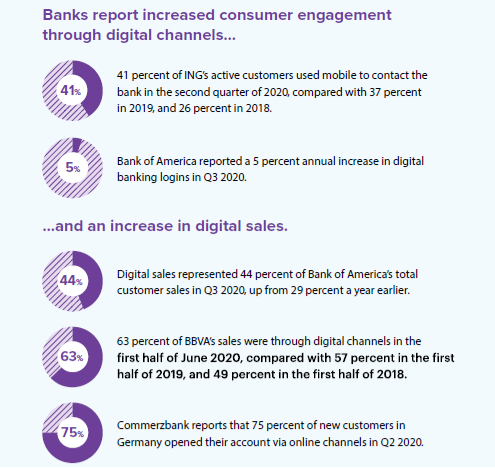

Banks have encouraged consumers to engage with them through digital channels. Migrating low-value and process-driven interactions to digital channels while retaining high value and more complex client activity in branches meant they saved costs while protecting personal relationships with customers. This has led to a gradual 3-4% shrinking of branch networks in much of the developed world, although in some markets closures have been more extensive. Although banks had some success, customer adoption of digital channels was slow for all but the most basic banking activities. Certain customer segments still visited their branches for things they could easily do online and even the most tech-savvy customers still liked the comfort of opening new accounts, resolving issues, or receiving advice about complex products face to face.

Banks have encouraged consumers to engage with them through digital channels. Migrating low-value and process-driven interactions to digital channels while retaining high value and more complex client activity in branches meant they saved costs while protecting personal relationships with customers. This has led to a gradual 3-4% shrinking of branch networks in much of the developed world, although in some markets closures have been more extensive. Although banks had some success, customer adoption of digital channels was slow for all but the most basic banking activities. Certain customer segments still visited their branches for things they could easily do online and even the most tech-savvy customers still liked the comfort of opening new accounts, resolving issues, or receiving advice about complex products face to face.

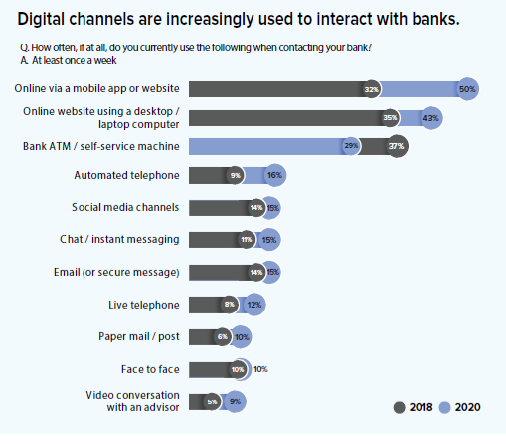

As much as 50% of consumers now interact with their banks through mobile apps or websites at least once a week; 2 years ago, this was just 32%. The volume of in-branch transactions in the US has decreased by 30-40%. Digital engagement across all consumers is significantly higher than at pre-pandemic levels. Digital migration also accelerates commoditization and jeopardizes trust for banks that sudden upswing in digital engagement could be both a blessing and a curse.

PERSONALIZATION

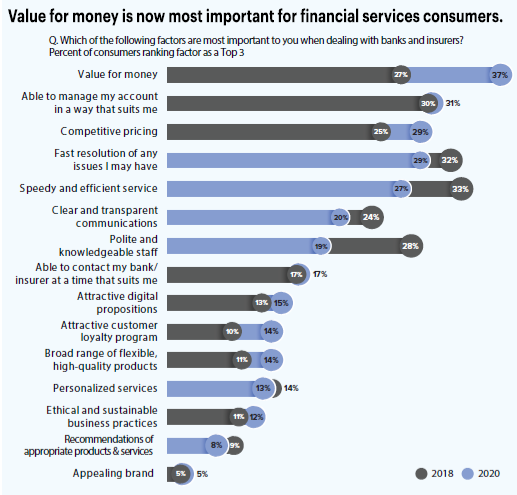

Customers value price competitiveness while dealing with their banks, and insurance customers have ranked value for money in the first place. Some 2 years ago, value for money was only in 5th place. And although primary bank account switching activity is low, those who have switched in the past 12 months are most likely to say that a better price or value was their main reason for doing it. For the people who have not switched, price and value are the main factors that might cause them to do so in the next 12 months.

The rising importance of price is partly a consequence of the sudden shift from relatively buoyant macroeconomic conditions to the economic stress and uncertainty associated with covid. It is also due to the growing digitization of the consumer banking experience, which causes customers to increasingly view it as a commoditized product. Personalized solutions can wean consumers off price This change is likely to be less permanent than some other shifts in consumer behaviour because consumers will become less focused on price as economic uncertainty diminishes.

Financial institutions could offer personalized solutions such as savings tips based on spending patterns. Pioneers find this type of digitally enabled personalization appealing. Interest grows in personalized digital banking consumers as they continue to show little appetite for the abstract concept of personalized experiences: just 13% of the survey respondents said this is important to them, which is slightly lower than 2 years ago. But banks cannot discount personalized offerings completely.

CUSTOMER TRUST DECLINES

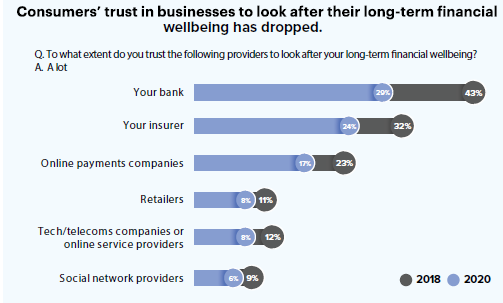

Customers’ faith in banks and other major institutions has plummeted. Just 29% of the consumers said they trust their banks ‘a lot’ to look after their long-term financial wellbeing, compared with 43% 2 years ago. The replacement of human interaction with digital channels, and the resulting breakdown of personal connections, also reflects a broader decrease in trust in major institutions.

Customers’ faith in banks and other major institutions has plummeted. Just 29% of the consumers said they trust their banks ‘a lot’ to look after their long-term financial wellbeing, compared with 43% 2 years ago. The replacement of human interaction with digital channels, and the resulting breakdown of personal connections, also reflects a broader decrease in trust in major institutions.

Consumer trust has also fallen when it comes to insurers, payments companies, retailers, tech companies and social media platforms – although to a smaller extent than banks. The positive news for banks is that even with that bigger slump in the trust, they are still trusted more than these other major institutions.

This could be a result of the high-profile consumer data breaches in the past 2 years and the tightening of data protection regulation. Both have raised consumers’ awareness of data privacy issues. Banks can rebuild trust by forgoing at-risk ‘bad revenue’ (such as overdraft charges) to show increased commitment to customers’ interests, by providing services that genuinely look after customers’ long-term financial wellbeing and by delivering tangible benefits in return for sharing their data. Some have already started to do this. For example, Bank of America recently made a long-term commitment to offering neobank-style overdraft support features that it had introduced during the pandemic.

This could be a result of the high-profile consumer data breaches in the past 2 years and the tightening of data protection regulation. Both have raised consumers’ awareness of data privacy issues. Banks can rebuild trust by forgoing at-risk ‘bad revenue’ (such as overdraft charges) to show increased commitment to customers’ interests, by providing services that genuinely look after customers’ long-term financial wellbeing and by delivering tangible benefits in return for sharing their data. Some have already started to do this. For example, Bank of America recently made a long-term commitment to offering neobank-style overdraft support features that it had introduced during the pandemic.

EMERGENCE OF NEOBANK

Primary bank account switching has slowed in the past 2 years. Just 3.8% of consumers have switched their primary account in the past 12 months, compared with 6.7% 2 years ago. Switching activity remains primarily driven by the pioneers, with 7% switching their primary account in the past 12 months compared with just 1% of traditionalists. The reason for this is a combination of a natural slump in switching to neobanks following an initial surge of early adopters; consumers’ existing banks improving their capabilities, especially their online banking apps; and a

Primary bank account switching has slowed in the past 2 years. Just 3.8% of consumers have switched their primary account in the past 12 months, compared with 6.7% 2 years ago. Switching activity remains primarily driven by the pioneers, with 7% switching their primary account in the past 12 months compared with just 1% of traditionalists. The reason for this is a combination of a natural slump in switching to neobanks following an initial surge of early adopters; consumers’ existing banks improving their capabilities, especially their online banking apps; and a  natural suppression of switching by the pandemic. This decline has occurred in a period in which, the pandemic aside, switching has never been easier: open banking regulation in certain markets smoothens the switching process and technical advances have dramatically reduced the time it takes to open a new account. Although switching has never been easier, measuring switching activity has become more complex because some consumers increasingly accessorize their main bank account with other accounts for specific purposes, so there are more multi-banked customers. Nearly 27% of consumers have opened a new account (including primary and secondary accounts) in the past 12 months, compared with 24% two years ago.

natural suppression of switching by the pandemic. This decline has occurred in a period in which, the pandemic aside, switching has never been easier: open banking regulation in certain markets smoothens the switching process and technical advances have dramatically reduced the time it takes to open a new account. Although switching has never been easier, measuring switching activity has become more complex because some consumers increasingly accessorize their main bank account with other accounts for specific purposes, so there are more multi-banked customers. Nearly 27% of consumers have opened a new account (including primary and secondary accounts) in the past 12 months, compared with 24% two years ago.

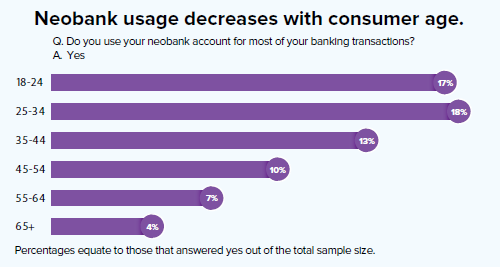

SWITCHING BANKS

In this context, the process of switching may take longer and be less apparent in banks’ data, with a consumer initially opening a new account and using it to process some payments, before gradually increasing the volume of payments they process and eventually having their salary paid into the new account. Consumers’ interest in neobanks is cooling – for now neobanks have continued to gain market share in the past 2 years. Today, 23% of surveyed consumers have a neobank account, up from 17% two years ago. That said, just 12% use a neobank account for the majority of their transactions, and uptake is driven by specific consumer groups: 24% of pioneers, for instance, use a neobank account for the majority of their banking transactions, compared with just 4% of traditionalists.

Despite the recent growth, consumers’ enthusiasm for neobanks is lukewarm. For example, consumers that have a neobank account are most pleased with its convenience, simplicity, and price point, rather than its novel features, personalized offerings, or the brand in general. And those who have a neobank but do not use it for most of their transactions say their primary reason for that is that they are happy with their existing bank. Traditional banks’ new digital offerings may slow the growth of neobanks.

NEOBANKS MAY BECOME FAVOURITES

Will consumer interest in neobanks reignite when the economic picture improves? It may. A more favorable economic outlook could lead consumers away from what they perceive to be the stability of traditional banks, and neobank features such as cheap currency exchange will become more attractive if consumers are able to travel more in the future. Plus, as time goes on, each neobank becomes less and less ‘neo’, which may reassure customers who were previously put off by their shorter track record.

In Australia, for example, NAB and Commonwealth Bank both recently launched interest-free credit cards in response to the success of ‘buy now, pay later’ provider Afterpay. And although neobanks’ lack of expensive real estate should enable them to be cost competitive with traditional banks, pressure to hit profitability and identify new revenue streams, such as charging for current accounts, may negate that advantage. For neobanks, some consumer segments are currently out of reach Some consumer segments have a strong aversion to neobanks. For example, 62% of traditionalists say nothing would tempt them to open a neobank account, compared with just 8% of pioneers. That is also true of 57% of those aged over 65, compared with just 10% of those aged 18-24.